Last week I

told you about how, in the years leading up to the new assignment my husband

and I took in East Africa, all Wycliffe trainees had to pass a more-than-strenuous

survival course called Jungle Camp. (If you missed it, click on Angst over anticipating our three-month orientation course.)

What I didn’t

tell you last week was the part of Jungle Camp that paralyzed me with fear. Each

participant had to be prepared at all times for any eventuality because at a

time unknown to them, one by one they’d receive a tap on the shoulder and be

led away into the wilderness where he or she would have to survive, alone, for 24

hours or more.

At the moment

of the shoulder tap, whatever a trainee had—in his pocket, in her water

canteen, tools or supplies he had (knife, compass, rope, etc.), whatever clothes

she had—would have to suffice.

Can you imagine?! You’d have no way to get help in

an emergency. Even without emergencies, you’d have to build a fire, catch and

butcher and cook your own meat, find a source of water, and coexist with jungle

creatures all night, hearing their calls, listening to their footsteps getting

closer and closer, hearing a snake slither through the underbrush.

I could

understand the rationale behind such training—Bible translator friends of ours

in South America, for example, used such skills to set up their work in

isolated areas within Stone Age-type cultures.

In addition, in

South America I had worked with two young women who fled from guerrilla

soldiers and had to survive in the jungle, on the run, awaiting their rescue. (You’ll

want to read about that in Chapter 39 of my new memoir, Please, God, Don’t Make Me Go: A Foot-Dragger’s Memoir.)

Yes, I

understood the importance of such rigorous training.

But I dreaded

having to go through such training myself!

However, before

Dave and I set out for Africa, I received good news! Wycliffe’s orientation

courses had changed over the years, at least in East Africa. No longer were

they such strenuous survival courses. Instead, they focused mainly on

orientation to our new countries and cultures.

Dave and I

would still have to rough it for three months—living in tents, listening to

wild creatures in the night, hauling water, cooking over a fire, and hiking, among

other challenges.

Our

orientation, called Kenya Safari, would be easier than Jungle Camp, but I

dreaded it because I was not athletic, possessed no aspiration for adventure,

and loathed roughing it. Moreover, I had already paid my membership dues and

joined the over-the-hill society.

With only a vague idea of what to expect during the orientation, I did know I’d never experienced

anything like it and that I’d need more strength, stamina, and tenacity—physical,

mental, emotional, and spiritual—than I’d ever needed before.

For two years I had prayed, and prayed, and prayed, and psyched myself up for Kenya Safari but, by on the day of our departure, I still didn’t have a lot of confidence in myself.

Nevertheless,

somehow (well, not somehow, but by God’s grace) my worries and doubts coexisted

with faith that God would get me through if only I’d depend on Him and

cooperate with Him.

The Bible says,

“In quietness and confidence shall be your strength” (Isaiah 30:15, NKJV). I

told God I’d keep my mouth shut and take care of the quietness part if He’d

take care of the confidence part.

So, armed with

a chocolate bar and my friend Esther’s instructions on how to stare down a

leopard, on September 9 Dave and I set out on our three-month orientation,

Kenya Safari.

With a clenched

jaw, mixed emotions, and plenty of jitters, I gave God a stern reminder that I

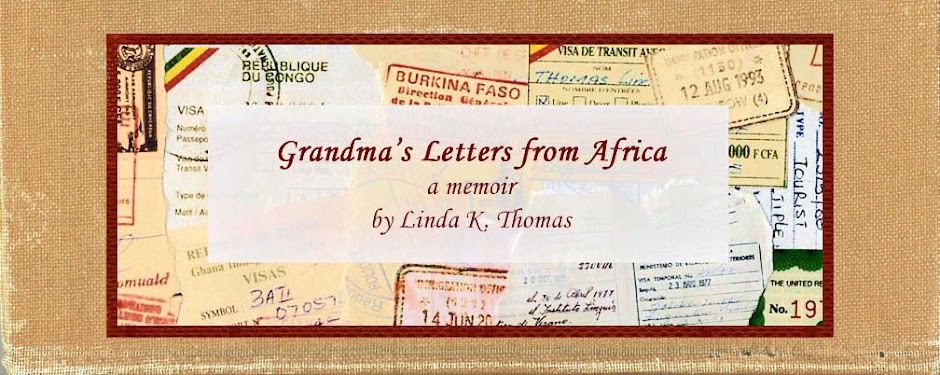

was counting on Him. (from Chapter 1, Grandma’s Letters from Africa)

“. . . Maybe courage is not at all about the absence of fear

but about obedience even when we are afraid,” writes Katie Davis Majors.

“Maybe courage is trusting when we don’t know what is next,

leaning into the hard and knowing it will be hard, but more, God will be near,”

she continues. “He is the God Who Will Provide. He will provide His presence,

His strength, or whatever He decides we most need.”